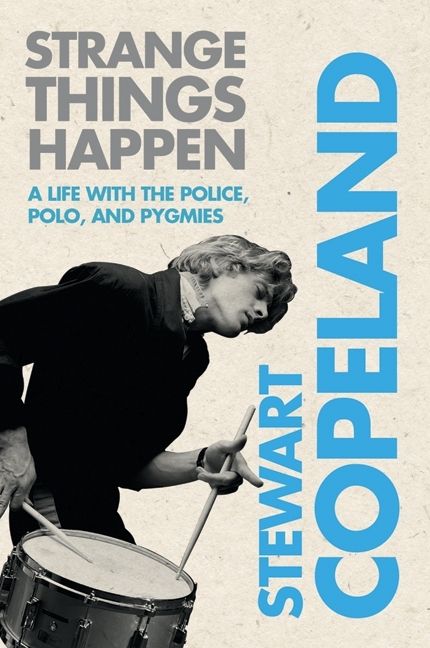

Stewart Copeland released a memoir in 2009, Strange Things Happen: A Life With the Police, Polo, and Pygmies and narrated the audiobook. I somehow overlooked this at the time but discovered the print edition when wandering through an unfamiliar library, an activity I recommend if only for that very reason.

It’s best to start by describing what isn’t in the book. Except for a chapter on what it was like to become famous, he mostly skips his heyday with the Police, probably because he documented that with his film Everyone Stares. He also focuses on his professional rather than personal life. He devotes maybe a sentence to Sonja Kristina as his first wife, spilling more ink on their business relationship with Curved Air. In his book Wild Thing brother Ian detailed the circumstances of Stewart’s losing his virginity after his drumming debut; Stewart also recalls the gig but is discrete about the liaison. Ian’s 2006 death merits no mention. Even a story about playing Crusaders and Saracens as a kid growing up in Lebanon primarily serves as a set-up for writing Stewart's first opera about the Crusades. It’s also not a straight-up chronology, although he does provide dates for each exploit he recounts, useful to anyone wanting to generate a timeline.

Copeland does make his scope explicit. The episodic chapters recall the assortment of adventures he had leading up to, parallel to, and as a result of those early years with the Police. The book conveys his own sense of wonder at everything he’s done, including the patriotism that boiled up in him as he played polo against Prince Charles one July 4th. The polo chapter focuses on his brief time as a member of the leisure class, but almost everything else is about his work as a musician. And this is a strong theme: although he made his mark on the world as a drummer, he is a well-rounded musician/composer for whom percussion is just one aspect of his identity. His composing an opera sounds far less ludicrous after learning about his sideline in film scoring and his traditional music education in college; as someone who struggled through several semesters of music theory myself, I particularly appreciated his difficulties with parallel fifths.

Late in the book, he dives into the Police reunion in the Aughts, the events with Sting and Andy Summers that led up to it and anecdotes from the world tour. Those looking for dirt will find it here, especially the clash of egos. He is very respectful of his bandmates’ talents but also aware of refusing to be dictated to. After decades away from his old band, time spent when he was either clearly in charge or subordinate to others, he and his bandmates chafe at the adjustment to being peers in an alleged democracy. The civil war reaches a truce when they recognize that their reunion will be finite and they can more happily settle in to the remainder of the tour. That attitude and some technical aspects he goes into explain why I was much more impressed with their show during the last stretch of the tour than in its first year.

A few themes emerge. Copeland clearly embraces life and is game for all sorts of musical escapades, even acknowledging that serving as judge for a British TV singing competition was naff but fun. He’s aware of the Police’s place in the world as fake punks. He’s also humble about his musical shortcomings and has no axe to grind. He has a lot of affection for Sting and Andy and takes equal responsibility for the difficulties among them.

The book is an entertaining read, but the audiobook is a more entertaining listen. The latter offers a distinct advantage over the print: interstitial music at the end of each chapter. I’ve read many books about musicians rather than listening to audiobooks so I don’t know if this is unusual. But many chapters left me wonder, “I wonder what that sounded like,” only to be followed with the answer to that question. Likely due to rights issues, the only music snippets are Copeland’s sole compositions rather than any collaborations with others.

Copeland’s turns of phrase suggest an authentic voice rather than the generic tone of a ghost writer. As a favorite examples, bandmates are “bandsters” and Sting’s offspring are “Stingsters.” Read much of his press and you’ll start to recognize some stock answers. He acknowledged devising a set of off-repeated stories when promoting his first opera, and some anecdotes and stories he uses in the book have cropped up in interviews promoting Gizmodrome, his latest musical project. This is an observation more than a criticism. His character comes through in his writing. He's got a lot of character, and it's a likeable one.

It’s best to start by describing what isn’t in the book. Except for a chapter on what it was like to become famous, he mostly skips his heyday with the Police, probably because he documented that with his film Everyone Stares. He also focuses on his professional rather than personal life. He devotes maybe a sentence to Sonja Kristina as his first wife, spilling more ink on their business relationship with Curved Air. In his book Wild Thing brother Ian detailed the circumstances of Stewart’s losing his virginity after his drumming debut; Stewart also recalls the gig but is discrete about the liaison. Ian’s 2006 death merits no mention. Even a story about playing Crusaders and Saracens as a kid growing up in Lebanon primarily serves as a set-up for writing Stewart's first opera about the Crusades. It’s also not a straight-up chronology, although he does provide dates for each exploit he recounts, useful to anyone wanting to generate a timeline.

Copeland does make his scope explicit. The episodic chapters recall the assortment of adventures he had leading up to, parallel to, and as a result of those early years with the Police. The book conveys his own sense of wonder at everything he’s done, including the patriotism that boiled up in him as he played polo against Prince Charles one July 4th. The polo chapter focuses on his brief time as a member of the leisure class, but almost everything else is about his work as a musician. And this is a strong theme: although he made his mark on the world as a drummer, he is a well-rounded musician/composer for whom percussion is just one aspect of his identity. His composing an opera sounds far less ludicrous after learning about his sideline in film scoring and his traditional music education in college; as someone who struggled through several semesters of music theory myself, I particularly appreciated his difficulties with parallel fifths.

Late in the book, he dives into the Police reunion in the Aughts, the events with Sting and Andy Summers that led up to it and anecdotes from the world tour. Those looking for dirt will find it here, especially the clash of egos. He is very respectful of his bandmates’ talents but also aware of refusing to be dictated to. After decades away from his old band, time spent when he was either clearly in charge or subordinate to others, he and his bandmates chafe at the adjustment to being peers in an alleged democracy. The civil war reaches a truce when they recognize that their reunion will be finite and they can more happily settle in to the remainder of the tour. That attitude and some technical aspects he goes into explain why I was much more impressed with their show during the last stretch of the tour than in its first year.

A few themes emerge. Copeland clearly embraces life and is game for all sorts of musical escapades, even acknowledging that serving as judge for a British TV singing competition was naff but fun. He’s aware of the Police’s place in the world as fake punks. He’s also humble about his musical shortcomings and has no axe to grind. He has a lot of affection for Sting and Andy and takes equal responsibility for the difficulties among them.

The book is an entertaining read, but the audiobook is a more entertaining listen. The latter offers a distinct advantage over the print: interstitial music at the end of each chapter. I’ve read many books about musicians rather than listening to audiobooks so I don’t know if this is unusual. But many chapters left me wonder, “I wonder what that sounded like,” only to be followed with the answer to that question. Likely due to rights issues, the only music snippets are Copeland’s sole compositions rather than any collaborations with others.

Copeland’s turns of phrase suggest an authentic voice rather than the generic tone of a ghost writer. As a favorite examples, bandmates are “bandsters” and Sting’s offspring are “Stingsters.” Read much of his press and you’ll start to recognize some stock answers. He acknowledged devising a set of off-repeated stories when promoting his first opera, and some anecdotes and stories he uses in the book have cropped up in interviews promoting Gizmodrome, his latest musical project. This is an observation more than a criticism. His character comes through in his writing. He's got a lot of character, and it's a likeable one.

No comments:

Post a Comment